Pluralistic Practice: A Diverse, Client-Centered Approach

Share

How often have you gone into a session with an intervention in mind, only to find this ambition was swept aside as a different theme entirely emerged in the room?

There’s nothing wrong with plans. Often these evolve naturally from past conversations, agreed-upon goals, or insights generated through professional development or supervision, but they can also reduce clients' self-determination when we hold on to them too strongly. As we learn to embrace the often non-linear nature of clients' progress and trust in our own skills, many practitioners find it helpful to imagine there could be a compass to guide them in this space. The bad news is, there is no substitute for our own clinical judgment. But there are themes we encounter and certain interventions which may be suited toward these in a pluralistic sense.

Learning at times to let go of plans can create anxiety for many practitioners. Professional accountabilities within often disempowering, risk-averse legislative frameworks combined with our longing to help others and impart practical tools can trigger defenses that often render us inflexible. Similar to the “righting reflex,” adopting rigid plans without considering and having access to a broader, more flexible toolkit renders emergent phenomena unhelpful—a mere distraction from our own goals. But defenses like these are understandable—counseling is an emotional experience, and we are not robots. The high prevalence of burnout and the potential for experiences of vicarious trauma remain unique to few professions, one of which is ours. Recognising certain triggers of our own as well as both maladaptive and adaptive patterns of responding may therefore be essential to maintain professionalism and ensure adequate self-care.

Clients' unexpected behaviour including new content or goals reflects the very essence of progress; it is new learning to be considered and opportunities for intervention. In the same way even the most detailed risk assessment may be rendered redundant by life changes between sessions, so too can our plans. Pluralistic psychotherapy represents a flexible, inclusive, and adaptive framework that centres the client’s unique needs and preferences. Recognising the value of all modalities and practices, it also reduces the need for planning by offering a toolkit that draws upon everything that is useful. Doing this fosters a therapeutic relationship that is dynamic, collaborative, and client-centered, aligning with the client’s broader life context (Prochaska & Norcross, 2013). Central to pluralism is a celebration of diversity, a commitment to inclusivity, and a strong focus on the relationship between therapist and client. This flexibility and adaptability are particularly valuable in today’s therapeutic landscape, where clients seek unique, individualized solutions.

Key Benefits of Pluralistic Practice

- Interventions that fit “just right…” - An individualized approach enables therapists to choose from a range of methods depending on the client’s goals and experiences. This helps ensure that therapy remains relevant and effective, fostering a sense of empowerment (Cooper & McLeod, 2011).

- Champions cultural competence - It encourages therapists to be mindful of their own cultural backgrounds, biases, and positions of privilege, and how their identity affects the therapeutic process. This awareness can foster more culturally sensitive practices and a more inclusive space for clients (Sue, 2010).

- Empowers marginalized voices - Pluralism recognizes inherent inequalities and strives to create a more equitable therapeutic space. The therapist’s role is not only to listen to but also to actively validate the client’s voices (McLeod, 2019).

- A tool for every occasion - Pluralism integrates an array of evidence-based therapies. It does not favor one, but draws from various practices to provide the most effective interventions.

- Evidence-based efficacy - Studies indicate that when clients are given the choice of treatment methods, they experience greater satisfaction and are more likely to engage actively in therapy (Swift & Callahan, 2009).

- Robust, flexible approach - Varied approaches like this target multiple dimensions of the self, addressing mind and body while respecting the complexity of trauma. Among others, somatic, parts, and cognitive approaches each offer tools to support healing and transformation (Hopper, Bassuk, & Olivet, 2010; van der Kolk, 2014; Levine, 2010).

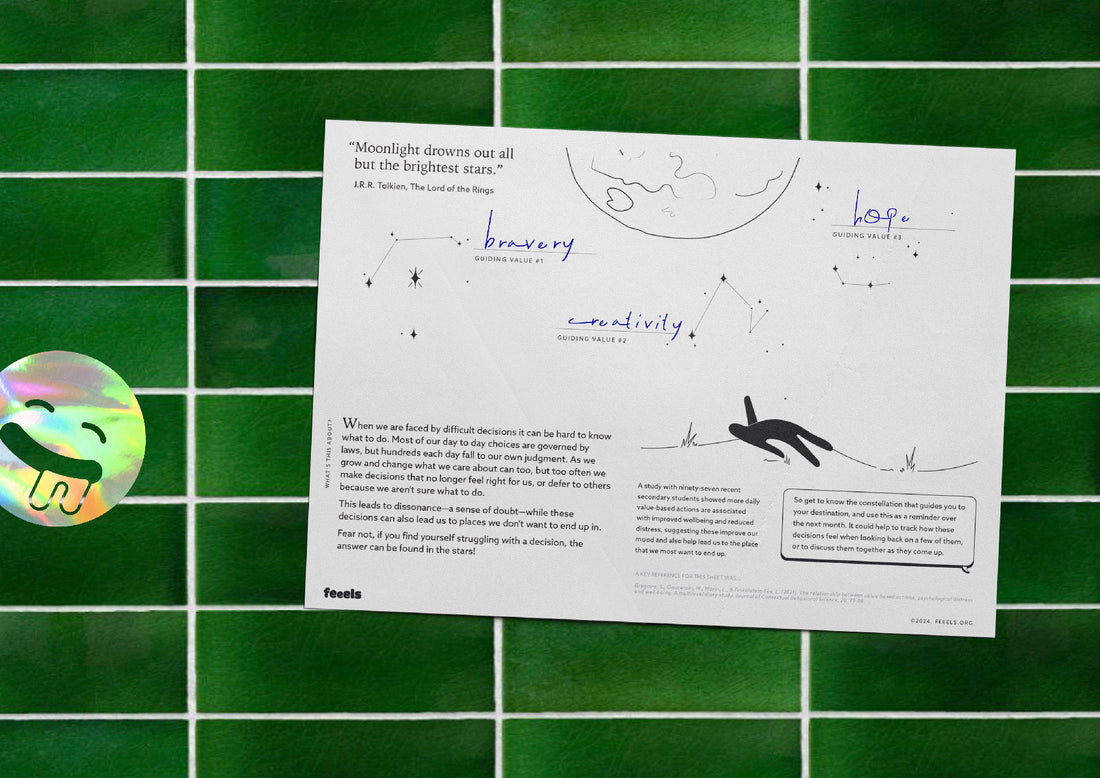

Embodying Pluralism using Feeels Resources

Our Feeels resources are a prime example of pluralism in practice, as they draw upon a rich variety of therapeutic modalities and contemporary psychological frameworks. Each resource we provide is a fusion of modern, diverse, and evolving ideas, allowing us to build upon the strengths of various modalities. This enables practitioners to create a comprehensive, individualized experience tailored to the unique needs and goals of every client. Some of the key therapeutic practices we integrate into our resources include:

- Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT): Helps clients identify and challenge unhelpful thought patterns, promoting emotional and behavioural changes (Beck, 2011).

- Emotion-Focused Therapy (EFT): Supports clients in exploring and reshaping their emotional experiences, fostering healthier emotional connections (Greenberg, 2002).

- Compassion-Focused Therapy (CFT): Encourages self-compassion, particularly for clients dealing with shame and self-criticism, enhancing resilience (Gilbert, 2010).

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT): Focuses on accepting difficult emotions and aligning actions with core values to build psychological flexibility (Hayes, 2019).

- Ego State Therapy: Aids trauma recovery by healing fragmented parts of the self, combined with other trauma-informed techniques for a comprehensive approach (Watkins, 1997).

- Somatic Practices: Integrates body awareness techniques to promote emotional regulation and reduce tension, essential for trauma survivors (Levine, 2010).

- Polyvagal Theory: Enhances trauma-informed care by helping clients regulate their autonomic nervous system responses, fostering long-term well-being (Porges, 2011).

Feeels kits have modular elements that can be mixed and matched to suit your needs in the moment — the Feeels starter bundle is designed to be a general toolkit covering some of each of the practice approaches mentioned above.

By weaving diverse and modern therapeutic practices together, we create resources that make them ideal for eclectic practitioners or those wishing to explore this. Their alignment with common themes enables practitioners to exercise flexible judgment in the therapeutic space and draw upon those tools which may be most relevant to each client. As for pluralism in general - well, we think it’s something worth considering for any practitioners who identify with some of the things we discussed, or who just get excited about new modalities and emerging evidence like we do. Who knows - it might even lead to a new found love.

Disclaimer:

All content in our blogs is meant for entertainment and educational purposes only and is not intended to serve as a substitute for clinical judgment. Practitioners should always rely on their professional expertise when making therapeutic decisions.

References

Beck, A. T. (2011). Cognitive Behavior Therapy: Basics and Beyond (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press.

Cooper, M., & McLeod, J. (2011). Pluralistic Counselling and Psychotherapy. SAGE Publications.

Gilbert, P. (2010). The Compassionate Mind: A New Approach to Life’s Challenges. New Harbinger Publications.

Greenberg, L. S. (2002). Emotion-Focused Therapy: Coaching Clients to Work Through Their Feelings. American Psychological Association.

Hayes, S. C. (2019). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: The Process and Practice of Mindful Change. Guilford Press.

Hopper, E. K., Bassuk, E. L., & Olivet, J. (2010). Homelessness, trauma, and adversity: Implications for understanding and responding to the needs of people who are homeless. The Open Health Services and Policy Journal, 3(2), 137-151.

Levine, P. (2010). In an Unspoken Voice: How the Body Releases Trauma and Restores Goodness. North Atlantic Books.

McLeod, J. (2019). An Introduction to Pluralistic Counselling and Psychotherapy. McGraw-Hill Education.

Porges, S. W. (2011). The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, and Self-Regulation. Norton & Company.

Prochaska, J. O., & Norcross, J. C. (2013). Systems of Psychotherapy: A Transtheoretical Analysis. Cengage Learning.

Sue, S. (2010). Microaggressions and Marginality: Manifestation, Dynamics, and Impact. John Wiley & Sons.

Swift, J. K., & Callahan, J. L. (2009). The efficacy of psychotherapy integration: A meta-analytic study. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65(5), 454-466.

van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. Viking.

Watkins, E. (1997). Ego States: Theory and Therapy. W. W. Norton & Company.